Christians who worship on Sunday base this practice on the belief that Christ arose from the tomb on Sunday. Jews and Christians who worship on Saturday do so because it is the seventh day of the week. Both parties base their belief, and thus their practice, on an assumption. The assumption is that because the progression of days was not changed at the time the Julian calendar transitioned to the Gregorian, the modern week is identical to the Biblical week. Therefore, the “logical conclusion” is that Saturday is indeed the Bible Sabbath and Sunday is the day on which Christ arose from the grave. The facts of the Julian calendar itself, however, prove this assumption is false.

A well-known adage is that those who forget history are doomed to repeat the mistakes of history. Likewise, those who have never learned the facts of calendar history have built an entire belief structure on a faulty foundation: the assumption that weeks have cycled continuously and without interruption ever since Creation. It is of vital importance to all, regardless of their religion, to study the history of the Julian calendar. Assembling the missing puzzle pieces of historical fact reveals when a continuous weekly cycle of seven days became the standard measurement of time – and it was not at Creation.

The calendar of the Roman Republic was based on lunar phases. Pagan Roman priests, called pontiffs, were responsible for regulating the calendar. Because the pontiffs could also hold political office, it provided opportunity for abuse. Intercalating1an extra month could keep favored politicians in office longer, while not intercalating when necessary could shorten the terms of political opponents.

By the time of Julius Cæsar, months were completely out of alignment with the seasons. Julius Cæsar exercised his right2as pontifex maximus3(high priest) and reformed what had become a cumbersome and inaccurate calendar.4

In the mid-1st century B.C. Julius Cæsar invited Sosigenes, an Alexandrian astronomer, to advise him about the reform of the calendar, and Sosigenes decided that the only practical step was to abandon the lunar calendar altogether. Months must be arranged on a seasonal basis, and a tropical (solar) year was used, as in the Egyptian calendar . . . . 5

Notice that Sosigenes' big innovation was an abandonment of lunar calendation:

The great difficulty facing any [calendar] reformer was that there seemed to be no way of effecting a change that would still allow the months to remain in step with the phases of the Moon and the year with the seasons. It was necessary to make a fundamental break with traditional reckoning to devise an efficient seasonal calendar.6

To bring the new calendar into alignment with the seasons required adding an additional 90 days to the year. This was done in 45 B.C., creating a year of 445 days. "This year of 445 days is commonly called by chronologists the year of confusion; but by Macrobius, more fitly, the last year of confusion."7The first puzzle piece in establishing the truth of the calendar, is to realize that the Julian week of 45 B.C., did not look like the Julian week when Pope Gregory XIII modified it, and thus did not look like the modern Gregorian week of today. This is the first assumption made by both Jews and Christians, regardless of the day on which they worship. 8

The Julian calendar, like the calendar of the Republic before it, originally had an eight-day cycle.

The Roman eight-day week was known as internundinum tempus or "the period between ninth-day affairs." (This term must be understood within the context of the ancient Roman mathematical practice of inclusive counting, whereby the first day of a cycle would also be counted as the last day of the preceding cycle.9)The "ninth-day affair" around which this week revolved was the nundinæ, a periodic market day that was held regularly every eight days. 10

Early Julian calendars were not constructed in grids as are modern calendars, but the dates were listed in columns, with the days of the week designated by the letters A through H.11For example, January started with day "A" and would proceed through the eight days of the week, with the last day of the month being day "E." Unlike the Hebrew calendar, the Roman calendar had a continuous weekly cycle. Because January ended on day "E", February began on day "F". Likewise, February ending on day "A" started March off on day "B":

A k12 Jan F k Feb B k Mar B G C C H D D A E E, etc. B, etc. F, etc.

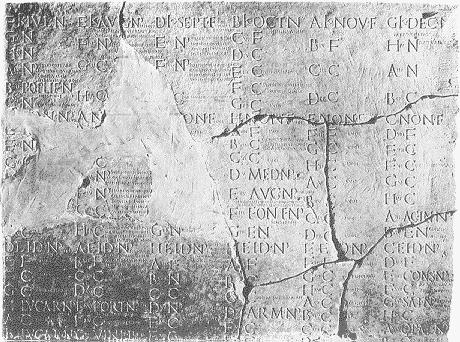

Following is a reconstruction13of the Fasti Antiates, the only known pre-Julian calendar still in existence14dating from the 60s B.C. found at the site of Nero's villa in Antium.

Fasti Antiates – reconstruction of the only known pre-Julian calendar in existence.

This calendar was painted on plaster with the letter A painted red to indicate the start of the week. The months are arranged in 13 columns. January, on the left, begins on day "A" and ends on day "E". At the bottom of each column are large Roman numerals showing the number of days in that month. The far right hand column is the 13th, intercalary month. Additional letters appear beside the week-day letters. These indicated what sort of business could or could not be conducted on that day.

All examples of Julian fasti, or calendars, date from the time of Augustus 15 (63 B.C. – 14 A.D.) to Tiberius (42 B.C. – 37 A.D.) If the assumption is correct that Saturday is the Bible Sabbath because the weekly cycle was not interrupted at the calendar change from Julian to Gregorian, then this should be easily proven from the early Julian calendars still in existence. An example of a Julian fasti is preserved on these stone fragments and provides the second, confirming piece of the puzzle in establishing the truth of calendar history. The eight-day week is clearly discernible on them verifying that the eight-day week was still in use by the Romans during and immediately following the life of Christ.

It is important to remember that the Biblical week as an individual unit of time defined in Genesis 1, consisted of only seven days: six working days followed by a Sabbath rest on the last day of the week. The eight-day cycle of the Julian calendar was in use at the time of Christ. However, the Israelites would not have kept the seventh-day Sabbath on the eight-day weekly cycle of the Julian calendar. This would have been idolatry to them. Even when the Julian week shortened to seven days, it still did not conform to the weekly cycle of the Biblical week nor did it resemble the modern week in use today.

The decline of the eight-day Roman week was caused by two factors: A) the expansion of the Roman Empire16which exposed the Romans to other religions and led, in turn, to B) the rise of the cult of Mithras.17The role Mithraism played in restructuring the Julian week is significant for it was a strong competitor of early Christianity.18

It seems as if some spiritual genius having control over the pagan world had so ordered things that the heathen planetary week should be introduced just at the right time for the most popular Sun cult of all ages to come along and exalt the day of the Sun as a day above and more sacred than all the rest. Surely this was not accidental.19

Under these two factors, the Julian week began a centuries-long evolutionary process that ended in the week as it is known today. The original seven-day planetary week is the third and final piece of the puzzle proving that Saturday is not the Bible Sabbath, nor Sunday the first day of the Biblical week. This transformation took several hundred years. Franz Cumont, widely considered to be a great authority on Mithraism, links the acceptance of the seven-day week by Europeans to the popularity of Mithraism in pagan Rome:

It is not to be doubted that the diffusion of the Iranian [Persian] mysteries has had a considerable part in the general adoption, by the pagans, of the week with the Sunday as a holy day. The names which we employ, unawares, for the other six days, came into use at the same time that Mithraism won its followers in the provinces in the West, and one is not rash in establishing a relation of coincidence between its triumph and that concomitant phenomenon.20

In Astrology and Religion Among the Greeks and Romans, Cumont further emphasizes the pagan origins and recent adoption of a seven-day week with its holy day being Sunday:

"The pre-eminence assigned to the dies Solis [day of the Sun] also certainly contributed to the general recognition of Sunday as a holiday. This is connected with a more important fact, namely, the adoption of the week by all the European nations.21

The immense significance of this for Christians is found in the fact that Sunday cannot be the day on which Christ arose from the dead, because Sunday did not exist in the Julian calendar of Christ's day. Nor can Saturday be the Biblical seventh-day Sabbath because the pagan planetary week originally began on Saturday.

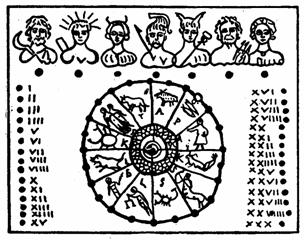

The following drawing of a stick calendar found at the Baths of Titus (constructed A.D. 79 – 81) provides further proof that neither the Biblical Sabbath nor the day of Christ's resurrection can ever be found using the Julian calendar. The center circle contains the 12 signs of the zodiac, corresponding to the 12 months of the year. The Roman numerals in the left and right columns indicate the days of the month. Across the top of the stick calendar appear the seven planetary gods of the pagan Romans.

|

| Roman Stick Calendar |

Saturday, (or dies Saturni – the day of Saturn) was the very first day of the week, not the seventh. As the god of agriculture, he can be seen in this preëminent position of importance, holding his symbol, a sickle. Next, on the second day of the pagan planetary week, is seen the sun god with rays of light emanating from his head. Sunday was originally the second day of the planetary week and was known as dies Solis. The third day of the week was dies Lunæ (day of the Moon – Monday). The moon goddess is shown wearing the horned crescent moon as a diadem on her head. The rest of the gods follow in order: dies Martis (day of Mars); dies Mercurii (day of Mercury); dies Jovis (day of Jupiter); and dies Veneris (day of Venus), the seventh day of the week.22

When the use of the Julian calendar with its recently adopted pagan planetary week spread into northern Europe, the names of the days dies Martis through dies Veneris were replaced by Teutonic gods.23Mars' Day became Tiw's Day (Tuesday); Mercury's Day became Woden's Day (Wednesday); Jupiter's Day became Thor's Day (Thursday); and Venus' Day became Friga's Day (Friday.)24The influence of the pagan astrological day-names is still seen today. Latin-based languages, such as Spanish, retain astrological names for Monday through Friday, with the Christian influence being seen in their words for Sunday (Domingo, or Lord's day) and Saturday (Sabado, or Sabbath.)

According to Rabanus Maurus (A.D. 776-856), archbishop of Mainz, Germany, Pope Sylvester I attempted to rename the days of the planetary week to correspond with the names of the Biblical week: First Day (first feria), Second Day (second feria), etc25. Bede, the "Venerable", (A.D. 672-735), renowned English monk and scholar, also reported Sylvester's attempts to change the pagan names of the days of the week. In De Temporibus, he stated: "But the holy Sylvester ordered them to be called feriæ, calling the first day the ‘Lord's [day]'; imitating the Hebrews, who named [them] the first of the week, the second of the week, and so on the others."26The astrological names, however, were too deeply ingrained. While the official terminology of the Roman Catholic Church remains Lord's Day, Second Day, Third Day, etc., most countries clung in whole or in part to planetary names for the days.

The astrological influence is obviously even more pronounced around the fringes of the Roman Empire, where Christianity arrived only much later. English, Dutch, Breton, Welsh, and Cornish, which are the only European languages to have preserved to this day the original planetary names of all the seven days of the week, are all spoken in areas that were free of any Christian influence during the first centuries of our era, when the astrological week was spreading throughout the Empire.27

"The ecclesiastical style of naming the week days was adopted by no nation except the Portuguese who alone use the terms Segunda Feria etc."28

The fact that both the Julian calendar and the pagan planetary week have been accepted for use by Christians reveals an amalgamation of Christianity with paganism of which the apostle Paul warned when he wrote:

For the mystery of iniquity doth already work: only he who now letteth 29will let, until he be taken out of the way. And then shall that Wicked be revealed, whom the Master shall consume with the spirit of his mouth, and shall destroy with the brightness of his coming: Even him, whose coming is after the working of Satan with all power and signs and lying wonders, And with all deceivableness of unrighteousness in them that perish; because they received not the love of the truth, that they might be saved. And for this cause Yahuwah shall send them strong delusion, that they should believe a lie; That they all might be damned 30who believed not the truth, but had pleasure in unrighteousness.31

The pagan planetary week, like the Julian calendar that adopted it, is irreparably pagan. Historical facts reveal that neither the Biblical Sabbath nor the Biblical First Day can be found using the modern calendar. If it is important to worship on a specific day, then it is also important to know which calendar to use and when the change in calendation occurred. It must always be remembered that when one worships reveals whom one worships: the Eloah of Creation, or the god of this world that is the leader of rebellion against the Creator. Each Deity/deity has His/his own calendar by which to be worshipped. Both Saturday and Sunday (as well as Friday) are pagan worship days.

Which calendar will you use to establish your worship day?

_________________________________________________

See also: Julian Calendar History (Video)