Modern Sabbatarians insist that Saturday is the Sabbath of the Bible because they believe that the seven-day week has cycled without interruption ever since Creation. One reason for this belief is the fact that when the Julian calendar changed to the Gregorian calendar in 1582, no days of the week were lost. Thursday, October 4, 1582, on the Julian calendar was followed by Friday, October 15, on the new Gregorian calendar. Therefore, it is assumed, because no days were "lost" when the calendars transitioned from Julian to Gregorian, the modern week is identical to the Biblical week.

This assumption is proven false in the historical facts of the Julian calendar itself. The calendar of the Roman Republic, like all ancient calendars, was originally based on lunar cycles. Pagan Roman priests, called pontiffs, controlled the calendar by announcing the beginning of months.

|

| Julius Cæsar |

In the mid-1st century B.C. Julius Cæsar invited Sosigenes, an Alexandrian astronomer, to advise him about the reform of the calendar, and Sosigenes decided that the only practical step was to abandon the lunar calendar altogether. Months must be arranged on a seasonal basis, and a tropical (solar) year used, as in the Egyptian calendar . . . .3

Notice that Sosigenes’ big innovation was an abandonment of lunar calendation.

The great difficulty facing any [calendar] reformer was that there seemed to be no way of effecting a change that would still allow the months to remain in step with the phases of the Moon and the year with the seasons. It was necessary to make a fundamental break with traditional reckoning to devise an efficient seasonal calendar.4

To bring the new calendar back into alignment with the seasons required adding an additional 90 days to the year, which ever after became known as the Year of Confusion. However, the Julian calendar of 45 B.C., even the Julian calendar of Christ’s day, did not look like the Julian calendar when Pope Gregory XIII modified it, and thus did not look like the Gregorian calendar of today. There was no Saturday (or seventh-day Sabbath at the end of the week) on the original Julian calendar.

The Julian calendar, like the calendar of the Republic before it, originally had an eight-day cycle. Every eighth day was a nundinæ, or market day. The calendars were not constructed in grids as are modern calendars, but the dates were listed in columns. For example, January started with day "A" and would proceed on through the eight days of the week (A through H), ending the month at day "E".

Unlike the Hebrew calendar, the Roman calendar had a continuous weekly cycle throughout the year, with a little adjustment at the end of the year. Because January ended on day "E", February began on day "F". Likewise, February ending on day "A" started March off on day "B":

| A k Jan | F k Feb | B k Mar |

| B | G | C |

| C | H | D |

| D | A | E |

| E, etc. | B, etc. | F, etc. |

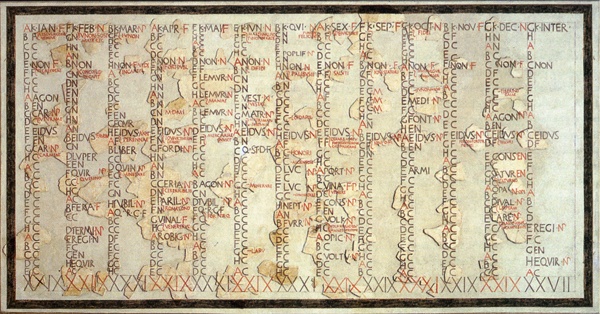

Following is a reconstruction of the Fasti Antiates, a pre-Julian calendar dating from the 60s B.C. found at the site of Nero’s villa in Antium. The letter A was painted red to indicate the start of the week.

Reconstruction of Fasti Antiates, the only calendar of the Roman Republic still in existence.5

There are thirteen columns. January, on the left, begins on day "A" and ends on day "E". At the bottom of each column are large Roman numerals giving the number of days in that month. The far right hand column is the 13th, intercalary month. Additional letters appear beside the week-day letters. These indicated what sort of business could or could not be conducted on that day. A "k" was painted beside the first day of every month. This stood for kalendæ.6

It is important to remember that the Biblical week as an individual unit of time defined in Genesis 1, consisted of only seven days: six working days followed by a Sabbath rest on the last day of the week. The eight-day cycle of the Julian calendar was in use at the time of Christ. However, the Jews would not have kept the seventh-day Sabbath on the eight-day weekly cycle of the Julian calendar. This would have been idolatry to them.

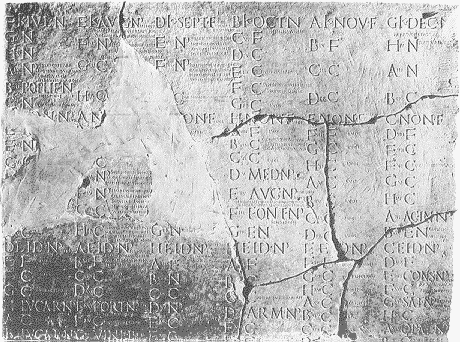

An example of a Julian calendar dating from the time of Augustus7 (63 B.C. – A.D.  14) to Tiberius8(42 B.C. – A.D. 37), is preserved on these stone fragments. The eight-day week is clearly discernible on them.

14) to Tiberius8(42 B.C. – A.D. 37), is preserved on these stone fragments. The eight-day week is clearly discernible on them.

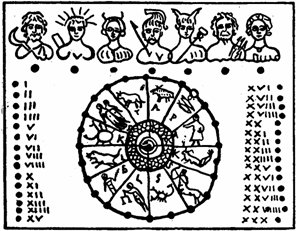

A later seven-day week Julian calendar, as seen in the following drawing of a stick calendar found at the Baths of Titus (constructed 79 – 81 A.D.), provides further proof that the Biblical Sabbath can never be found using the Julian calendar. The center circle contains the 12 signs of the zodiac, corresponding to the 12 months of the year. The Roman numerals to the left and right indicate the days of the month. Across the top of the stick calendar appear the seven planetary gods of the pagan Romans.9

Saturday (or dies Saturni – the day of Saturn)10 was the very first day of the week, not the seventh. As the god of agriculture, he can be seen in this preëminant position of importance, holding his symbol, a sickle. Next, on the second day of the pagan planetary week, is seen the sun god with rays of light emanating from his head. The second day of the week was originally dies Solis (the day of the Sun – Sunday). The third day of the week shows the moon goddess, with the horned crescent moon as a diadem on her head. Her day was dies Lunæ (day of the Moon – Monday). The rest of the days are represented by the other planetary gods, ending with dies Veneris (day of Venus, which in Northern European languages was changed to a Norse godess and became Friga’s day, or Friday.)11

Saturday (or dies Saturni – the day of Saturn)10 was the very first day of the week, not the seventh. As the god of agriculture, he can be seen in this preëminant position of importance, holding his symbol, a sickle. Next, on the second day of the pagan planetary week, is seen the sun god with rays of light emanating from his head. The second day of the week was originally dies Solis (the day of the Sun – Sunday). The third day of the week shows the moon goddess, with the horned crescent moon as a diadem on her head. Her day was dies Lunæ (day of the Moon – Monday). The rest of the days are represented by the other planetary gods, ending with dies Veneris (day of Venus, which in Northern European languages was changed to a Norse godess and became Friga’s day, or Friday.)11

Because the entire world has used the Gregorian calendar for hundreds of years, it is a frequently overlooked fact that in former times, not only did various countries use differing calendars, but there were also regional differences within individual countries. Although the seven-day planetary week became popularized in Rome with the rise of the cult of Mithras, it did not become official until Constantine standardized the week at the Council of Nicaea.12

In light of these facts, it is illogical to assume that the Gregorian Saturday is the Biblical Sabbath of Creation. It is true that the Julian calendar transitioned to the Gregorian calendar without any loss of days. However, it is also true that the Gregorian calendar, like the Julian calendar before it, is founded entirely upon a pagan system of calendation.

|

| Christopher Clavius (1538-1612) |

In his book, Romani Calendarii A Gregorio XIII P.M. Restituti Explicato, Clavius reveals that when the Julian calendar was made the ecclesiastical calendar of the Church at the Council of Nicaea, the Church deliberately rejected Biblical calendation and instead adopted pagan calendation. Referring to the differing systems of calendation used for determining the Biblical Passover versus the pagan substitute of Easter, Clavius states: "The Catholic Church has never used that [Jewish] rite of celebrating the Passover, but always in its celebration has observed the motion of the moon and sun, and it was thus sanctified by the most ancient and most holy Pontiffs of Rome, but also confirmed by the first Council of Nicaea."14The "Pontiffs" he is referring to are the ancient priests of Roman paganism.

Modern Christians have assumed that the Gregorian Saturday is the Biblical Sabbath. However, Christians who lived at the time the Julian calendar was enforced by civil legislation had no doubts or confusion over the matter: the "Sabbath" was calculated by the Biblical luni-solar calendar; the "Lord’s day" (Sunday) by the pagan solar calendar. As David Sidersky noted, "It was no more possible under Constance to apply the old calendar."15Apostolic Christians, however, did not obey the new edict.

At every step in the course of the apostasy, at every step taken in adopting the forms of sun worship, and against the adoption and the observance of Sunday itself, there had been constant protest by all real Christians. Those who remained faithful to Christ and to the truth of the pure word of [Yahuwah] observed the Sabbath of the [Master] according to the commandment, and according to the word of [Yahuwah] which sets forth the Sabbath as the sign by which [Yahuwah], the Creator of the heavens and the earth, is distinguished from all other [deities]. These accordingly protested against every phase and form of sun worship. Others compromised, especially in the East, by observing both Sabbath and Sunday. But in the west under Roman influences and under the leadership of the church and the bishopric of Rome, Sunday alone was adopted and observed.16

The Council of Nicaea (A.D. 321-325) outlawed the Biblical luni-solar calendar for ecclesiastical use, and supplanted the Julian calendar in its place, commanding that people everywhere "venerate"17 the day of the Sun.18 Some began to compromise. While many Christians clung to keeping the original Sabbath by the luni-solar calendar, others, with the rabbinical Jews, kept the seventh day of the Julian calendar: Saturday. Still others kept Saturday as well as Sunday. This did not satisfy the Church at Rome. She wanted everyone worshipping exclusively on Sunday. When the edict of Nicaea did not have the desired effect on the people, the Council of Laodicea was convened approximately 40 years later to enforce the acceptance of "the Lord’s Day" in place of the Biblical, lunar Sabbath.

In order, therefore, to the accomplishment of her original purpose, it now became necessary for the church to secure legislation extinguishing all exemption, and prohibiting the observance of the Sabbath so as to quench that powerful protest [against worship on Sunday]. And now . . . the "truly divine command" of Constantine and the council of Nicaea that "nothing" should be held "in common with the Jews," was made the basis and the authority for legislation, utterly to crush out the observance of the Sabbath of the [Master], and to establish the observance of Sunday only in its stead.19

Canon 29 of the Council of Laodicea demanded: "Christians shall not Judaize and be idle on Saturday, but shall work on that day; but the Lord’s day they shall especially honor, and, as being Christians, shall, if possible, do no work on that day. If however, they are found Judaizing, they shall be shut out from Christ."

It is important to know that the word "Saturday" has been supplied in the English translation. According to Catholic bishop, Karl J. von Hefele’s 20 History of the Councils of the Church from the Original Documents, the word used was actually "Sabbath" in both the Greek and the Latin and the word "anathema" (accursed) in place of "shut out". The Latin version clearly does not contain any reference to dies Saturni (Saturday) but instead uses Sabbato, or "Sabbath":

Quod non oportet Christianos Judaizere et otiare in Sabbato, sed operari in eodem die. Preferentes autem in veneratione Dominicum diem si vacre voluerint, ut Christiani hoc faciat; quod si reperti fuerint Judaizere Anathema sint a Christo.

Only in recent years, as the facts of history have been forgotten, has Saturday been assumed to be the Biblical Sabbath. When the Julian calendar was being enforced upon Christians for ecclesiastical use, no one at the time confused dies Saturni with Sabbato. Everyone knew that they were two different days by two distinct calendar systems.

A few days before His death, Christ made a profound statement that should be considered in the context of the controversy over true versus counterfeit calendars. He said, "Render therefore unto Cæsar the things which are Cæsar’s; and unto Yahuwah the things that are Yahuwah’s."21Christ was here establishing an important principle that was to govern every area of life. Worship does not belong to Cæsar. It belongs solely to the Creator.

An ancient proverb states: "He who controls the calendar, controls the world." Who controls you? The day on which you worship, calculated by the calendar you use, reveals which Deity/deity is in control of you. Worship on the true Sabbath is a sign of loyalty to our Creator. Only the Creator, the One in control of the sun, moon and stars, His calendar, has the right to tell His people when to worship and, by virtue of that right, to receive that worship.

__________________________________________________________________

Related Content:

-

Julian Calendar History (Video)

- Creator's Calendar (Content Directory)

- Changeling: Christians becoming Pagan

- The Crucifixion: Disproving the Continuous Weekly Cycle

- The Modern Seven Day Week: Exploring the History of a Lie

- Catholic Scholar Verifies Neither Saturday nor Sunday is Biblical Sabbath

1 Julius Cæsar had been elected Pontifex Maximus in 63 B.C. (James Evans, "Calendars and Time Reckoning," The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy, Oxford University Press, 1998, p. 165.)

2 "Pontifex Maximus" is now a title reserved exclusively for the pope. This is very appropriate as the Gregorian calendar now in use is both pagan and papal, being founded upon the pagan Julian calendar and modified by, and named after, a pope.

3 "The Julian Calendar", Encyclopedia Britannica.

4 Ibid., emphasis supplied.

5 Palazzo Massimo Alle Terme, ed. Adriano La Regina, 1998.

6 "Calendar," Encyclopedia Britannica online.

7 Cæsar Augustus, first Roman Emperor, is mentioned in the Bible. His levy of a tax led Mary and Joseph to Bethlehem in time for the birth of Christ. See Luke 2:1.

8 Tiberius succeeded Augustus as emperor in 14 A.D., retiring in 35 A.D. (Historic Figures, www.BBC.co.uk/history.)

9 The seven-day planetary week was adopted into the pagan Roman calendar with the rise of the cult of Mithras. (See Sunday in Roman Paganism, by R. L. Odom, Review & Herald Publ. Assoc., 1945.) The planetary gods thus became a permanent part of Julian calendation and pagan Roman culture.

10 For further information on the original planetary week governed by the seven planetary gods, see How Did Sunday Get It’s Name?, by R. L. Odom, at www.4angelspublications.com/books.php. Copyright, 1972, by Southern Publishing Assoc., used by permission.

11 J. Bosworth and T. N. Toller, Frig-dæg, An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary, 1898, p.337, made available by the Germanic Lexicon Project. See also "Friday" in Webster’s New Universal Unabridged Dictionary, 2nd edition, 1983.

12 See R. L. Odom’s "The Planetary Week in the First Century A.D.", Sunday Sacredness in Roman Paganism, Review and Herald Publish Assoc., 1944.

13 "When Gregory XIII reformed the calendar, the adjustment was made such that the vernal equinox should occupy the position assigned to it in the Easter tables, viz. March 21. These tables date . . . from about the third century. The important point is that this adjustment placed the vernal equinox on a date that is purely arbitrary and not necessarily related to the date on which the equinox fell when the revision of the calendar by Julius Cæsar was made." (Letter from Dr. H. Spencer-Jones, Astronomer Royal, Royal Observatory, Greenwich, London, to Grace Amadon, dated Dec. 28, 1938, Collection 154, Box 1, Folder 4, Center for Adventist Research, Andrews University, emphasis supplied.

14 Christopher Clavius, Romani Calendarii A Gregorio XIII P.M. Restituti Explicato, p. 54, as quoted in "Report of Committee on Historical Basis, Involvement, and Validity of the October 22, 1844, Position", Part V, Sec. B, p. 18, Collection 154, Center for Adventist Research, Andrews University.

15 Astronomical Origin of Jewish Chronology, Paris, 1913, p. 651.

16 A. T. Jones, The Two Republics, A. B. Publishing, Inc., 1891, p. 320-321.

17 Venerate: "to look upon with deep respect and reverence; . . . to regard as hallowed." Webster’s New Universal Unabridged Dictionary, 2nd edition, 1983.

18 "Constantine, Emperor Augustus, to Helpidius: On the venerable day of the sun let the magistrates and people residing in cities rest, and let all workshops be closed. In the country, however, persons engaged in agriculture may freely and lawfully continue their pursuits; because it often happens that another day is not so suitable for grain-sowing or for vine-planting; lest by neglecting the proper moment for such operations, the bounty of heaven should be lost." P. Schaff’s translation, History of the Christian Church, Vol. III, p. 75.

19 A. T. Jones, The Two Republics, A. B. Publishing, Inc., 1891, p. 321, emphasis supplied.

20 Karl Josef von Hefele (1809-1893), is a credible authority on the original word choice used at the Council of Laodicea. A German scholar, theologian and professor of Church history, educated at T?bingen University, and later bishop of Rottenburg, he had access to the Vatican archives and original documents.

21 See Matthew 22:21.